CITIZEN ARCHITECT

WHAT MAKES A CITIZEN ARCHITECT?

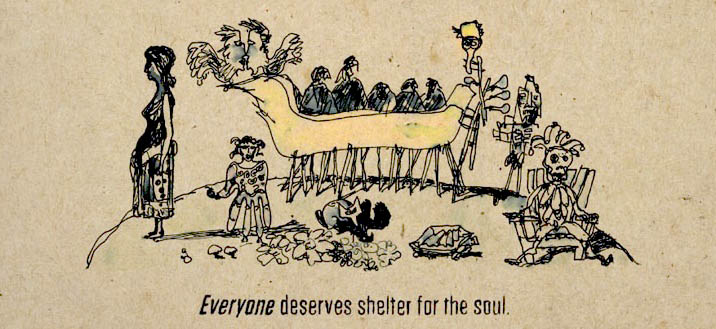

In the field of architecture, the term “Citizen Architect” is widely known—but outside the field, people might never have heard of it. On one hand, the meaning is clear. Citizen Architects should be good citizens, just like everyone else, and use their powers for good. On the other hand, though, architects have skills and training that can uniquely benefit society. That is, we make places where people live and work—and sometimes, people don’t have the necessary resources to build a fundamental, life-sustaining element. Shelter.

As a group of architects and designers, we routinely explore what it means to participate in our communities. There are loads of nonprofit efforts aimed at everything from affordable housing to building with sustainable materials to integrating green technologies. The bottom line of being a citizen, though, is personal. What and how much do we expect of ourselves? In what way can we harness our energy, our individual and collective brain-trusts, and our muscles?

WHAT CAN WE ACTUALLY DO?

Citizen Architects look to our inspirations—architects like the late Samuel “Sambo” Mockbee, who founded the Rural Studio at Auburn University. There, he taught students how to build affordable and interesting buildings in the rural South, buildings that inherently assisted and respected the disadvantaged population there. What worked about Mockbee’s approach is that he truly connected with the place and its inhabitants. His work was not driven by profit, and often recycled materials that others would consider waste. As our industry’s flag-bearer, he wished to make a profound impact in people’s lives.

Mockbee understood architecture’s obligation to include the margins of society. This is true in our home towns and it’s true across our global society. The challenge really comes from choosing specific projects that are doable and impactful and lasting. Without this focus, anyone could get overwhelmed with the vastness of the need. There are a lot more people and communities on the periphery than in our cultural power centers, and we cannot help everyone at once. We must start somewhere. We must start at home.

The best projects are participatory. This means that those impacted by the work identify what is needed, describe the environments that will be impacted, participate in the decision-making, and inform the design. BDT is in the process of committing time and money to such a pursuit. By committing to the practice—not just the theory—of being Citizen Architects, we are making internal change.

As more on this project develops, we will post on this blog. Our mission is to focus our contributions into a built work that embodies the principles of community service.

It’s sometimes a challenge for Creatives to shift out of their “design heads.” It’s fun to design cool buildings, experiment with shapes and color, ooh and aah over seemingly impossible structures built in amazing locations. But service means we join hands with our communities—and bring those coveted design elements into the everyday. Do only the most affluent get to have tall ceilings and inspiring views? Wouldn’t every child in every house benefit from a reading nook? Can’t any building take advantage of natural light?

So, how does it work? We get out of the cookie-cutter mindset—for buildings and for people. No one wants a cookie-cutter house, and no one wants a cookie-cutter architect. In every Citizen-related project that BDT engages, we look forward to bringing our deepest selves, our best ideas…and you.